Fearless and Bold: the story of our college

It’ll make you laugh. It’ll make you cry. But, best of all, it will make you proud of your alma mater. Jim Lightner’s big new book tells the story of our college, from its founding in 1867 as Western Maryland College to its 2002 name change to McDaniel College. It’s not always pretty but it is, as the book’s title concludes, Fearless and Bold. Originally published in the Summer 2007 edition of the The Hill magazine as, "Our Story."

College Historian James E. Lightner '59, professor emeritus of mathematics, is surrounded by handwritten notes gleaned from six years of research and writing the history of the college.

By Kim Asch

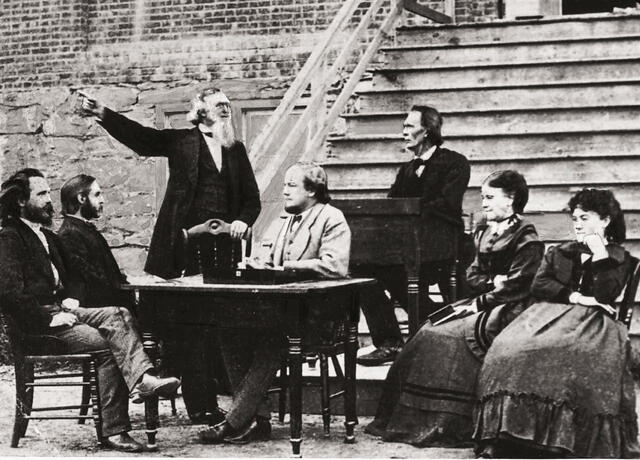

If the world worked strictly according to reason, the College we know and love on the Hill in Westminster probably would not exist today. It was just a year after the Civil War when an idealistic educator enlisted the aid of a Methodist Protestant minister in his ambitious plan to form a new college — a co-educational one, to boot — that would bring young men and women “out of darkness and into light.” Neither Fayette R. Buell nor James Thomas Ward had ever been to college and the pair knew nothing about running one. Money was also elusive.

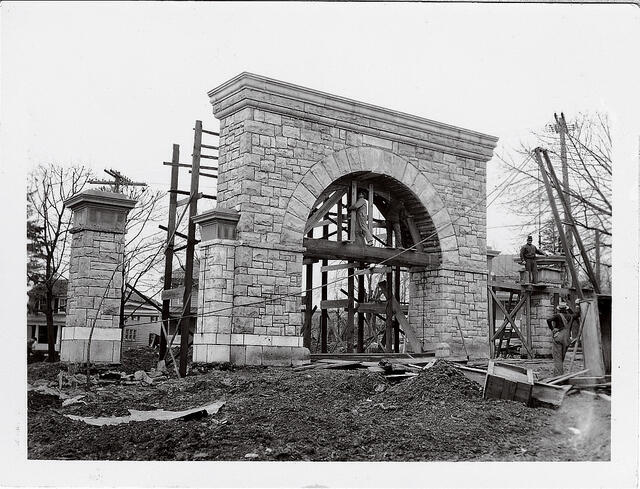

But even at an institution of higher learning, reason doesn’t always rule the day. At our College, there has always been an ample supply of passion and principle and perseverance to make possible the seemingly impossible. And so, despite its burden of debt and uncertainty, the College survived its infancy and has moved fearlessly forward, taking bold actions when necessary to ensure its healthy growth over 140 years.

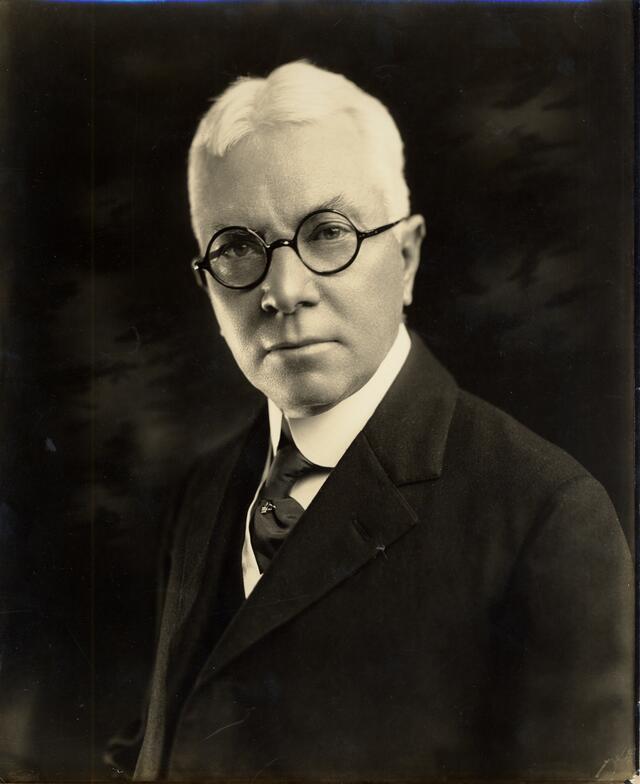

College Historian James E. Lightner ’59, professor emeritus of mathematics, spent six years doggedly researching and writing a meticulously detailed account of these events and introducing the living, breathing human beings behind them. His soon-to-be-published 650-page book, Fearless and Bold, contains more than 200 historic photos and a compelling narrative that he artfully wove together from a number of sources, including earlier written histories, minutes from trustee and faculty meetings, diaries, memoirs, scrapbooks, student newspapers and yearbooks and first-person interviews with senior alumni — including Sarah “Bootsie” Cockran Smith ’23, then the oldest living alumna — who shared memories of bygone years.

The book is a definitive, comprehensive reference; it’s also a good read that is rich with conflict, tragedy, humor and triumph. It was an ambitious project, to say the least, but Lightner was uniquely qualified for the job — he’d been in training for it the whole of his adult life.

“I think I was always a frustrated historian. Even as a student I was curious about the College people whose names I heard or read on buildings and I wanted to learn more about them,” says Lightner, who dug into research of the College’s roots as eagerly as if they were attached to his own family tree.

There had been other histories about the College, most notably The Formative Years, which documented its evolution between 1867 and 1947, written by Chemistry Professor Emeritus Samuel Schofield ’19 in conjunction with Marjorie C. Crain.

But Lightner aspired to produce something that spanned the whole life of the institution and that got beyond the facts and into the way it felt to be a member of the campus community, especially a student, during a particular decade.

Lightner officially retired in 1998. In 2000, he realized, “If I’m going to write this book I better get started.” His timing couldn’t be better, says trustee Don Rembert ’61, whose recently formed WMC Heritage Society is co-publishing the book with the College. He conceived the idea for the alumni group as a “grand reconciliation” in the aftermath of the College’s 2002 name change and the resulting furor among some who felt their alma mater had forsaken its past. The Society’s goal of “honoring the past while embracing the future” is served well by the book, Rembert says.

“The spirit of WMC lives and can flourish at McDaniel College,” says Rembert, who with his wife, Judy Ellis Rembert ’60, contributed $25,000 and assisted in raising more funds to cover the cost of publishing the book. (Lightner donated his time and efforts.) “It is a truth that Western Maryland College alumni can embrace.”

Lightner was teaching analytic geometry the Friday afternoon in 1963 when John F. Kennedy was shot. Someone knocked on the door of his Lewis Recitation Hall classroom to share the grim news that the President had been struck down. “My first reaction was, ‘Who would shoot Dr. Ensor?’” he says, remembering the way his mind immediately connected the word “president” with Lowell Ensor, the College’s top administrator at the time.

He shares the anecdote with a hint of self-deprecating humor, but also because the writer in him appreciates such telling detail. He explains, “The College is my milieu, you see?”

At 69, it is safe to say that Lightner is more familiar with the history of his alma mater than anyone else alive.

At 69, it is safe to say that Lightner is more familiar with the history of his alma mater than anyone else alive. His personal experience here spans half a century, starting with the fall semester of his freshman year in 1955 when he’d met with the now legendary Dean John D. Makosky ’25 and charted a course of study that would allow him to double major in mathematics and English with a minor in secondary education — and still graduate in three years, including summer school.

He’d been valedictorian at Frederick High School and liked working hard, taking every one of Makosky’s tough but enthralling classes in the English department and competently completing all of Clyde Spicer’s requirements in mathematics, surviving the Spicer curve. His entire college career he received just one letter grade lower than a “B.” It was a “C” in physics, a subject he confides, “just never clicked for me.”

Lightner was happily teaching high school mathematics and English, and had just earned a master’s degree from Northwestern University, when he received an irresistible invitation from President Lowell Skinner Ensor to join the mathematics department faculty in 1962. He was only 25 when he joined his former professors as their colleague.

“I remember how generously the faculty welcomed me back,” Lightner says. “[Biology professor] Jean Kerschner came over to say hello. ‘Welcome back, Jim. Now call me Jean,’ she said. And it’s been Jean ever since.”

As a professor, Lightner was at once demanding of and devoted to his students. “He was an extremely intense professor. He was in charge of the classroom — you didn’t mess around in his class. And he gave us a quiz every other day,” recalls Phil Meredith ’66, a chemistry major who took 18 credit hours of math with Lightner and went on to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry at Duke. “But he always had office hours, from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. every day, and he was always available to help people do the work. He’s probably one of the best teachers I ever had.”

A "Young Ladies" Dorm Room circa 1910. (Note the row of picture postcards around the wall near the ceiling, the wooden bed in the foreground and screen, which probably hides the "washstand.") During this era, the faculty's role in students' lives was still fairly oppressive. A Mr. Jones was given three demerits for whistling in the dining hall and female day students were regularly demerited for visiting boarding students in their rooms. But women were given permission to leave campus unchaperoned for short periods on Wednesday and Friday afternoons. This privilege was sometimes suspended for punishment. In June 1908, the senior boys and girls were allowed to take a walk together for an evening after summer until 8 o'clock, proper chaperones being provided.

During his 36-year tenure, Lightner’s meticulousness and organizational abilities were repeatedly called upon. He designed and directed the January Term; planned and led 13 study tours to England with English professor Ray Stevens; worked on grants for the Development office; designed the math proficiency program and oversaw it for a dozen years; became alumnus foundation member and an officer of the campus chapter of the nation’s most prestigious honor society, Phi Beta Kappa; and made sure Commencement ceremonies ran smoothly for 30 years as College Marshal.

Meredith especially admired Lightner’s ability to distinguish the relationship he had with students in class from the rapport he developed with them outside of class while participating in myriad extracurricular activities, such as singing in the College Choir or advising a fraternity.

“That’s sort of an amazing capability,” says Meredith, whose friendship with Lightner has deepened over the years to the point that his daughters know him as an honorary uncle.

Going to Homecoming with Lightner is “really a remarkable situation,” Meredith says, “because he knows everybody.” He adds that his former professor is the only person Meredith knows who can drive across the country and make stops to visit dozens of old College friends, former students or colleagues along the way.

When Lightner started writing the book, he asked his former student and longtime friend Meredith to be the first to read and edit each chapter. Meredith suggested that Lightner include a timeline of world events at the beginning of each chapter covering a different decade. That way it would not be “an insular history, but a history in context with what else was going on in the world around the College,” he says. He reminded Lightner that as a potential reader, he was not so much interested in the facts — though they were important for posterity — as the details of life in any given era.

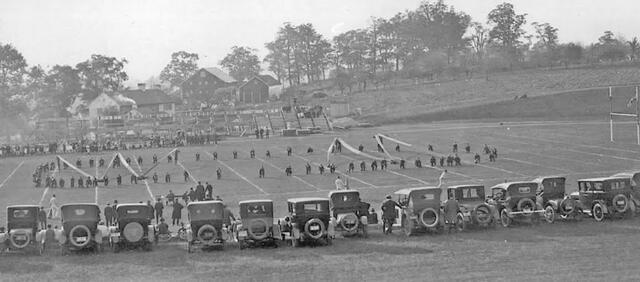

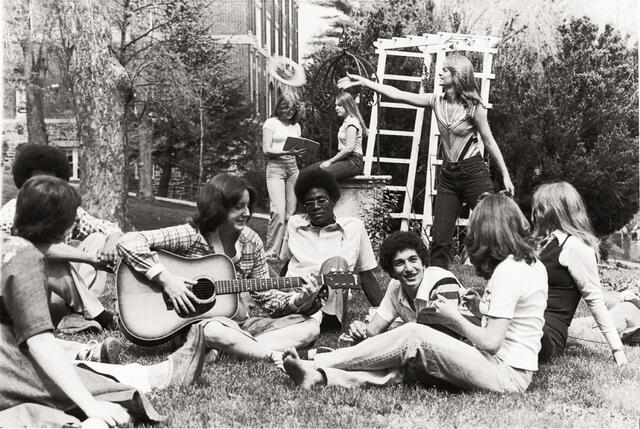

By 1975, campus diversity had increased, but there were still just 26 Black students enrolled. Two years before, a Black Student Union had formed. "The Commodores" appeared on campus at the 1975 Homecoming. In October 1976, an "evening in Black America" featured an appearance of Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee. During 1975-1976, Herbert Watson '76, a Black student, was elected president of the Student Government. The January term provided offerings in Black Literature, African American History, and Black and white relations.

Hence, the book includes all sorts of anecdotes about student high jinks and political protests and romances. There are snippets from the diaries of the first president about his fears and his proudest moments. There are unflinching accounts of a tragic sledding accident, tension over racial integration, the controversial decisions to disaffiliate with the Methodist Church and remove crosses from the chapels and, of course, the College’s name change in 2002.

Meredith observes that Lightner was never daunted by the monumental project of documenting it all. He was invigorated by it. “The College is a much better college than when I went to it,” Lightner concludes. “And I played a part in it, I guess.”