The roles of NATO and China in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: McDaniel expert weighs in

Francis Grice, associate professor of Political Science and International Studies, shared his insights on the current war between Russia and Ukraine, particularly how the evolving responses of NATO and China may signal the potential direction of the war.

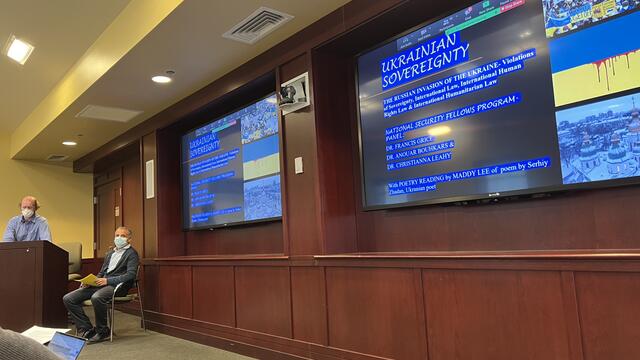

On March 8, 2022, Professor Francis Grice (left) presented on the response of NATO to Russia's invasion of Ukraine a panel hosted by the National Security Fellows program, accompanied by Political Science professors Christianna Leahy and Anouar Boukhars (seated, right).

Francis Grice, associate professor of Political Science and International Studies, shared his insights on the current war between Russia and Ukraine, particularly on the role of NATO and China as forces on either side of the conflict.

Outside of teaching courses on international law, relations in the Asia-Pacific, and security studies, Grice is the director of the National Security Fellows (NSF) program and leads the McDaniel delegation of the Model United Nations. On March 8, he spoke on a panel hosted by the NSF program about Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, alongside professors Christianna Leahy and Anouar Boukhars.

What more can NATO do?

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) convened a summit on March 24, exactly one month after Russia launched its invasion into Ukraine, but the outcome of the summit remains uncertain. NATO has, until this point, acted in a limited capacity befitting its role as a defensive alliance. It has primarily condemned Russia and coordinated NATO members that are independently providing aid to Ukraine, and it appears on track to continue in that way.

Grice says that many NATO nations are mainly concerned with determining contingency plans to enact if Russia escalates the conflict.

“NATO has already pursued less militaristic options, and it’s not going to admit Ukraine into NATO or enforce a no-fly zone,” he says. “The next thing for them to consider is what their reaction will be if Putin uses chemical or biological weapons.”

Even then, NATO’s options are limited. Grice describes a similar situation in Syria, when the Assad regime used chemical weapons against its citizens in 2013. While Syria was eventually forced to cede its stockpiles to the United Nations (U.N.), it otherwise garnered few consequences. And, despite official U.N. resolutions and condemnations, Syria continued to use banned chemical weapons.

“So, how can NATO make a cautionary threat and then follow through?” Grice says.

Although Ukraine has continued to thwart Russian advances, the country has suffered an immense humanitarian toll. While the international community, and Ukraine, have made attempts at diplomacy, implemented economic sanctions on Russia, and provided military support, an end to the conflict — and what that may look like — remains uncertain.

What is clear, says Grice, is that the conflict has evolved beyond Putin’s initial intentions. “We are increasingly seeing a move away from Russia expecting a quick victory and using precision weapons, toward tactics deliberately targeting civilians, with the goal being to depopulate large portions of Ukraine.

“That switch in strategy is notable for a number of reasons. For one, it suggests that Putin is preparing to dig in for the long term,” says Grice. “It speaks to a change in the character of the conflict. It switches NATO’s intentions from being purely about repelling an aggressor to responding to humanitarianism.”

The China question

China, which declared allyship with Russia not long before the war began, has remained an unknown element in the conflict. Grice notes that there have been both pro-Russia and anti-war sentiments from Chinese officials, which deviates from the typical unified messaging of China’s government.

The mixed messaging may be due to the changing nature of Russia’s invasion, which has unraveled China’s initial expectations.

“China envisaged that this would be a short, quick, bloodless war,” says Grice. “More of a coup d’état. Russia overwhelms the Ukrainians within days and places a puppet government in Ukraine. Then sanctions in the West would be similar to what they were after the 2014 invasion of Crimea — a slap on the wrist.

“That would have set a nice precedent for China to do the same with Taiwan, but now I think they’re facing a horror scenario, since sanctions on Russia are far, far more significant than China thought they were going to be. They’re facing active threats that if they move in to help Russia in a significant way, then those sanctions will be applied to them.”

Economic sanctions against China would likely have greater repercussions for the U.S. and other NATO allies than the sanctions on Russia.

“The threat from Russia is a militarily mutually assured destruction. With China, the threat is economically mutually assured destruction,” says Grice. “Our economic infrastructure is so intertwined with theirs that for us to impose significant sanctions on them would be to cause ourselves exponential pain to the point of economic ruin.”

While the U.S. and others could absorb those effects if the cause is great enough, it remains unlikely that China will become involved in the war between Russia and Ukraine, being less willing to endure the ostracization and economic impacts that Russia is currently facing. China also risks a change in regime if the country experiences sustained hardship after aiding Russia.

“If the U.S. economy or any of the NATO economies, which are all democracies, fall into economic ruin, we see a change of party in government,” Grice says. “If China plunges into economic ruin, we see a change in regime and the communist party is no more. They have a much lower tolerance for that kind of economic pain.”